The S.C. Supreme Court ruled a solicitor-run docket unconstitutional in a 2012 decision. But counties such as Beaufort are still using that method of deciding when cases are heard. (Photo by Reagin von Lehe)

Incarcerated people claiming innocence are in jail awaiting the day their trial will be called. If bail isn’t an option, they’re unable to work — they might lose their jobs and apartments, and their families will suffer without their support.

Those without bail have to make a decision — to plead guilty and compromise with jail time and/or probation or to request a speedy trial and stay in jail until the court is able to review their case. The waiting leads to overcrowding, costing cell space and taxpayer money.

South Carolina’s courts are more backed up than they’ve ever been, according to critics. There’s not an efficient-enough system or the right number of judges to give many defendants a speedy trial.

Attorney and former Charleston deputy solicitor Jack Sinclaire said solicitors, also known as prosecutors, and judges can’t agree on a management solution for the court docket — the order of cases being heard. The one thing they can agree on is that the current state of the docket isn’t sustainable.

“It’s a big, giant mess,” said Sinclaire, who said he’s not alone in his criticism of the system. “It’s been an issue for as long as I can remember,” but “it’s gotten three times worse than that now.”

Cases where defendants aren’t in jail can take up to two years to work through the courts. The more serious cases, such as murder, armed robbery and criminal sexual conduct, can take up to five years to get called into court, according to Sinclaire.

Allie Menegakis, a criminal defense lawyer and founder of S.C. for Criminal Justice Reform, said the issue isn’t new, but the pandemic exacerbated it.

Only 20% of new cases in South Carolina are resolved in a calendar year, while the remaining 80% roll over into the next, according to the Charleston County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council’s annual report. The amount of time it takes from arrest to court disposition — the final decision — was 415 days in 2015. By 2021, the number of days was 592. That’s a 177-day increase.

“I’d rather categorize it as (a delay) than a backlog,” Menegakis said. “A backlog insinuates that if it were running smoothly, then everything would be fine, which, in this case, it’s impossible for it to run smoothly because we don’t have rules in place.”

Menegakis practiced in Florida before moving to North Charleston, where she saw major issues in the court system. She founded SC4CJR, a non-profit organization that advocates for changes to the S.C. criminal justice system.

Defining what a speedy trial means is a problem and possibly the most impactful solution, according to Menegakis and her colleagues with SC4CJR.

Florida has legislation defining it. Misdemeanors and non-jail cases take up to 90 days from time of arrest to disposition, and for felonies or other incarceration cases, 175 days.

Menegakis remembers being in the courtroom daily from 8:30 a.m. to noon. She and her peers were presenting hundreds of cases a day in Florida courtrooms.

In Florida, a case from 2020 involving Eva Benefield’s father has gone viral.

She will be testifying in the murder trial. Her father, Doug Benefield, was shot and killed by her stepmother, who is claiming self defense but is charged with second-degree murder. Benefield said the case has been pushed back three months at a time over two years.

“Obviously, we want justice for my dad,” Benefield said. “The biggest inconvenience is really just, as much as we want justice, I also would just like to get his estate settle. And we can’t do any of that until after the trial is over.”

Two years may seem like a long time for the Florida case, but it’s a speedy dream compared to South Carolina.

“Two years to wait for a trial is exponentially better than it is here in South Carolina,” Menegakis said. “There are victims who have been waiting five years for justice to be brought, (and) defendants who have been stuck in jail more than five years waiting for their case to be brought to trial.”

Sometimes the delay in cases is beneficial for defendants — police officers leave the force, evidence gets lost, witness memories fade and, in turn, their case gets better with time, Sinclaire said. But for others, a speedy trial is imperative.

“But here’s the question: What’s a speedy trial?” Sinclaire said.

In South Carolina, there are one or two weeks of trials per month and only one or two cases are heard in a day, Menegakis said. She said there are months of wasted time where cases just sit in the docket.

Menegakis and her businesses partner, the state director of SC4CJR, Alesia Flores, said South Carolina was the only state in the country where prosecutors ran trial dockets, until the state Supreme Court ruled that unconstitutional in 2012.

Charleston and Richland counties since have converted to trial dockets set by judges. But other large counties such as Beaufort are behind on that front.

“The majority of the counties still practice under that really archaic type of docket control where a prosecutor determines when cases go to trial,” Menegakis said.

Regardless of how cases are put on the docket, Menegakis and Sinclaire agree more judges are needed to support the caseloads.

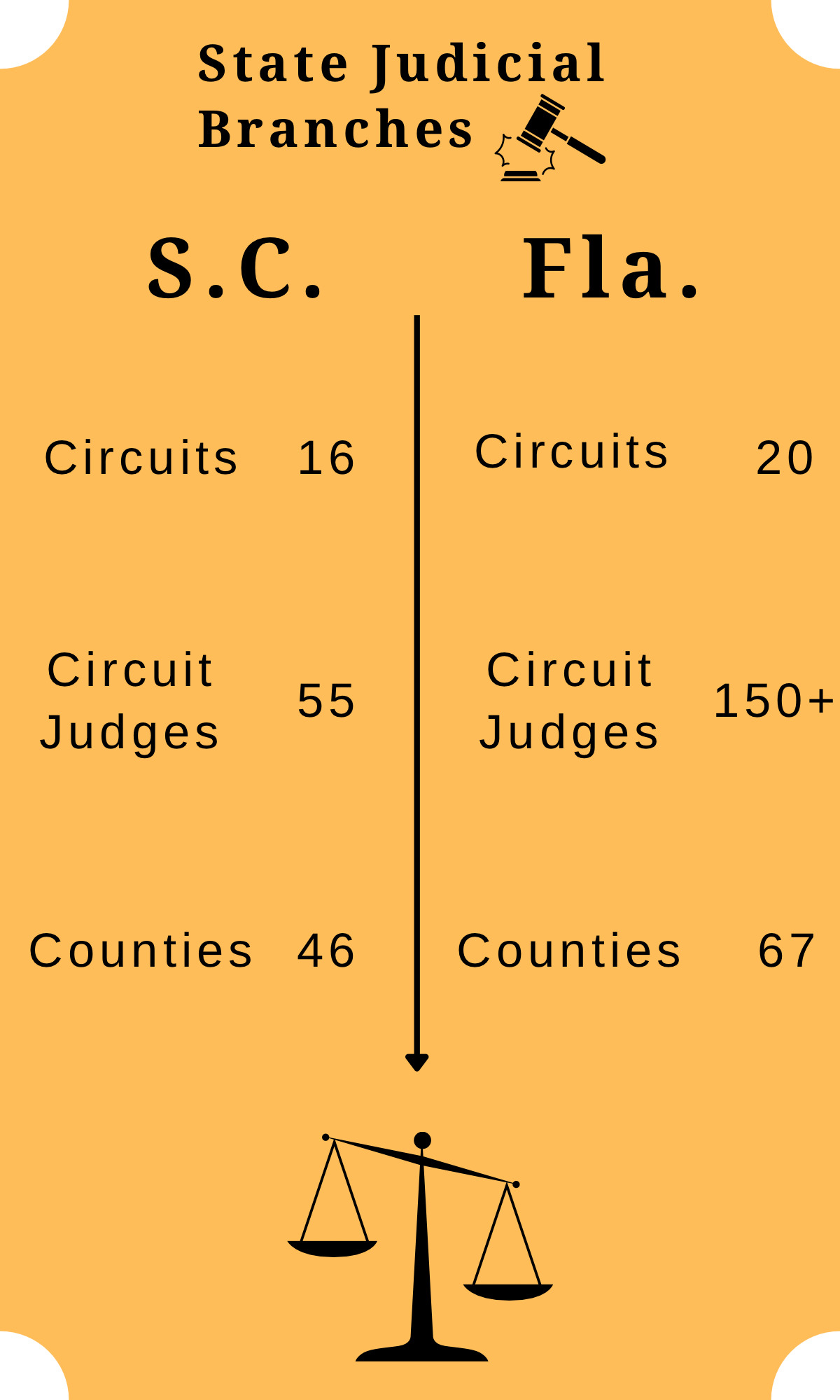

Florida has about two circuit judges per county, whereas South Carolina only has about 50 circuit judges for its 46 counties, which is slightly more than one per county.

Judges running dockets in South Carolina still isn’t a perfect system, critics say.

In South Carolina, the governor and legislators appoint judges. In Florida, some are appointed and some run in general elections. Menegakis said South Carolina needs to change its method of hiring judges to speed up the backlog.

Corruption and judge-shopping — favoring and waiting for a certain judge — are major issues that come from judges being appointed by lawmakers, Menegakis said.

Sinclaire and Menegakis said they don’t know if or when South Carolina’s court dockets will catch up.

“If we start putting rules in place, the court and the prosecution will be forced to abide by them, which, in turn, will make our due process system more efficient and … will decrease the amount of people that end up in our jails and prisons,” Menegakis said.

Allie Menegakis is a practicing criminal defense attorney who founded a nonprofit organization working toward change within the state’s legal system. (Photo courtesy of Allie Menegakis)

Jack Sinclaire is an attorney who has seen the trial docket grow “exponentially” since he was deputy solicitor in 1992. (Photo courtesy of Jack Sinclaire)

Eva Benefield said she doesn’t have many photos of herself with her father before he was killed. But she’s pictured here with him and her mother in front of their Christmas tree when she was younger. (Photo courtesy of Eva Benefield)

The size of South Carolina’s court system is not reflective of its population in comparison with Florida’s. (Graphic by Reagin von Lehe)