Native American and other minority art has been underrepresented throughout the Carolinas, but nonprofits and artists are seeking to change that narrative. Photo by: Daniella Ramirez

Public art representing Native American and minority communities may seem hard to come by in the Carolinas. However, nonprofits in Columbia and Charlotte are reaching out to artists to showcase their work.

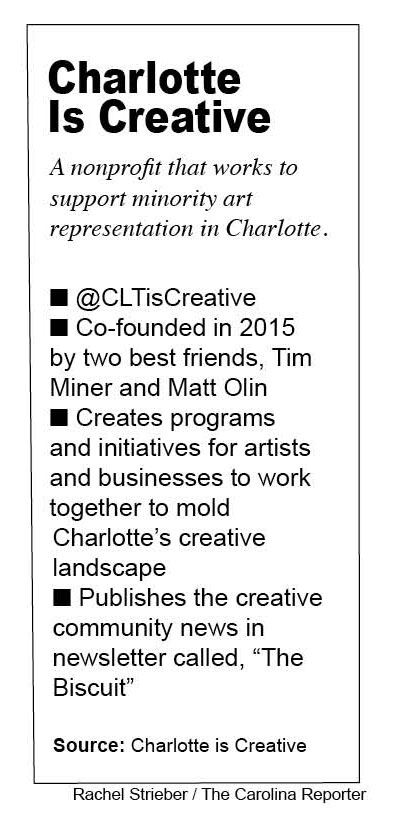

Charlotte is Creative helps the arts and business community work together to create a more vibrant city by supporting large or small businesses and minority artists.

“I think our approach, what makes us maybe not special, but different, is that we try everything we do from our meetings, to our media channel, to our microgrants, to Queen City quiz show, to trainings we do, it’s all in an effort to begin a relationship,” said Tim Miner, co-founder of the nonprofit. “It gives artists an easy way into getting to know us and getting to know other businesses.”

Miner said Charlotte’s biggest problem is, “racial equity and racial harmony.”

“We were just looking down the line and saying, ‘What small thing can we do to shine a light on this community in a different way?’” said Miner.

One Columbia, a nonprofit organization in Columbia, engages in similar efforts.

The nonprofit focuses on supporting and promoting tourism in Columbia, while also working with government and business associates to advise, amplify and advocate for the arts and history of the city.

Both organizations are embarking on initiatives to bring more creative “placemaking” to their communities.

Placemaking, “inspires people to collectively reimagine and reinvent public spaces as the heart of every community,” according to Project for Public Spaces, a New York-based nonprofit that works in partnership with communities to improve community spaces.

Charlotte is Creative seeks ways to help under-resourced communities by bringing artists into those communities. The organization does this through initiatives such as The Hug Microgrant program, a $250 grant offered to both nonprofit or for-profit creative initiatives in Charlotte.

“I think that we serve a role in the creative community in Charlotte, where we are working very hard to elevate artists of all different kinds,” said Miner.

Ricky Singh, a Charlotte artist and school principal, created the mural on the side of Queens Mini Mart on Beatties Ford Rd, where a shooting June 22 claimed the lives of four people. The mural depicts a bird plucking an egg from behind. That action symbolizes Sankofa, a metaphorical symbol from Ghana that means, “to look toward the future.”

Singh got permission from the property owners to create this mural for the community and those who died in the shooting.

Miner said the nonprofit also helped Charlotte artist Georgie Nakima, who painted two murals along Charlotte’s east side in East Town Market.

The horizontal-geometric mural represents, “creative placekeeping,” said Nakima in an interview with “The Biscuit,” Charlotte is Creative’s weekly newsletter. “Creative placemaking is about making a place. But, this has already been made. Creative placekeeping is honing in on what’s been here — the history and also the cultural impact.”

One Columbia features murals designed to encourage creativity as well.

In 2018, the “Growing Together” mural was created by Charmaine Minniefield and installed alongside artists Sean Irving and Zoe Jackson at Hyatt Park in Columbia.

The lively mural consists of African-American themes that relate to the fabric and flora of Hyatt Park.

Both Nakima and Minniefield were provided with funds by the Knight Foundation, a national foundation that creates funds for artists and institutions that help spread and reflect the diversity of cities.

With the help of One Columbia and Charlotte is Creative, both artists were able to receive the grants needed to create their art in their respective communities.

In 2014, along the Little Sugar Creek Greenway in Charlotte, the statue of Thomas “Kanawha” Spratt and King Haigler was placed as part of the Queen City’s Trail of History.

Chas Fagan, a Charlotte artist and sculptor, created the statue, which recognizes the peaceful relationship the Catawba Indian Nation and North and South Carolina settlers had in the 1750s.

Charlotte is Creative recognized the artist and statue in “The Biscuit.”

Part of the work that Miner does is try to help more demographics and to reach deeper and build up the resources they need to touch more populations — a problem that Columbia faces.

“We just wanted to lift up our city and the solution came out of that. And that might be what’s more replicable than taking the programs we’ve developed, which are developed for Charlotte or the Charlotte region, and then creating the Columbia version of that,” said Miner. “In time, gather information, talk to people, honestly listen and then start to generate your solutions based on what your set of challenges and what your setup assets are.”

One Columbia, by authorization of the city of Columbia, is in charge of “creative placemaking.”

Similar to Charlotte is Creative’s initiatives, One Columbia gives artists the opportunity to submit a form for public art commissions.

However, some Columbia artists still think South Carolina lacks in showcasing art that represents different cultures and minority communities.

Roy Paschal, a fine artist and Columbia native, created the public Native American Sculpture in Cayce.

“The Congaree tribe lived and prospered in this area, so when Cayce put out a call for art pieces with a ‘local feel,’ and I had always been interested in the history behind the Native Americans, I was led to do that piece,” said Paschal.

This piece depicts a Native American maiden, of the Congaree tribe, pouring water from two urns. One urn symbolizes the Saluda River, and the other represents the Broad River, which unite to form the Congaree River.

Paschal said that many eastern Native American tribes lost their identities and assimilated, which could explain why the art is less prevalent in South Carolina.

“When most people think of Native American, they think of the Western tribes, which had their own form of government and constant representation,” said Paschal. “Although the southeastern tribes have identities, they are no more, so they have no voice. They don’t fit the Hollywood concept of Native Americans.”

He believes that Native American representation through art in Columbia preserves that voice and history.

“I think [art] continues the story. Some people don’t even know about the Congaree tribe. It may cause them to be more inquisitive and learn about the history of the Native Americans along the eastern coast,” said Paschal.

Another Columbia artist, retired Lexington School District 4 teacher Trudith Schoblocher Dyer, wants South Carolina to step up its Native American art representation. She organized a small art exhibition of the Indigenous Women’s Alliance at the Nickelodeon Theater in Columbia in 2019.

“I do not see a sufficient amount of Native American art in our state. Today, we have a great deal of Native pride and we are trying to keep the customs, culture and traditions alive,” said Dyer. “I am from the Virginia Upper Mattaponi Indian tribe, so my regalia is different from the beautiful ribbon dresses of North Carolina and South Carolina.”

Some Columbia artists are working to address this issue.

Joshua Knight, a teaching associate at Coastal Carolina University, makes and sells art to symbolize both societal issues and his Native American heritage. Scorched Heritage is a sculpture he created in which he carved multiple totem poles into one and then set it on fire.

“It came from me doing a self-reflection, dealing with me coming up in the foster care system and not being able to express my Native American heritage,” said Knight. “My foster parents actually burned our home down, so I burned my totem pole.”

Visual and public art has become more popular as a way for artists to communicate societal messages important to them and members of their communities.

“I personally think the arts can have a dramatic effect on social justice,” said Knight. “Depending on the person doing the work and their popularity and the meaning behind the work, they could definitely have a big role and impact on anything doing with any topic.”

The statue of Thomas “Kanawha” Spratt and King Haigler stands near Morehead Street in Charlotte. Spratt played an essential role in developing land in the Charlotte region and created a peaceful relationship with Catawba King Haigler. Photo Credit: Daniella Ramirez

Ricky Singh created this memorial on the side of the Queens Mini Mart at 2120 Beatties Ford Road in Charlotte after a shootout left four people dead. Photo Credit: Daniella Ramirez

Georgie Nakima’s large-scale mural about “creative peacekeeping/placemaking” is located near Compare Foods on the N. Sharon Amity side in Charlotte. Photo Credit: Daniella Ramirez

This mural in Columbia’s Hyatt Park is titled “Growing Together,” by artist Charmaine Minniefield. Photo Credit: One Columbia’s Public Art Directory

Located in the West Columbia interactive art park in Cayce is this Native American Sculpture by Roy Paschal. Photo Credit: One Columbia’s Public Art Directory

South Carolina artist Joshua Knight created this Scorched Heritage sculpture in 2019. Photo Credit: Joshua Knight, ArtFields SC